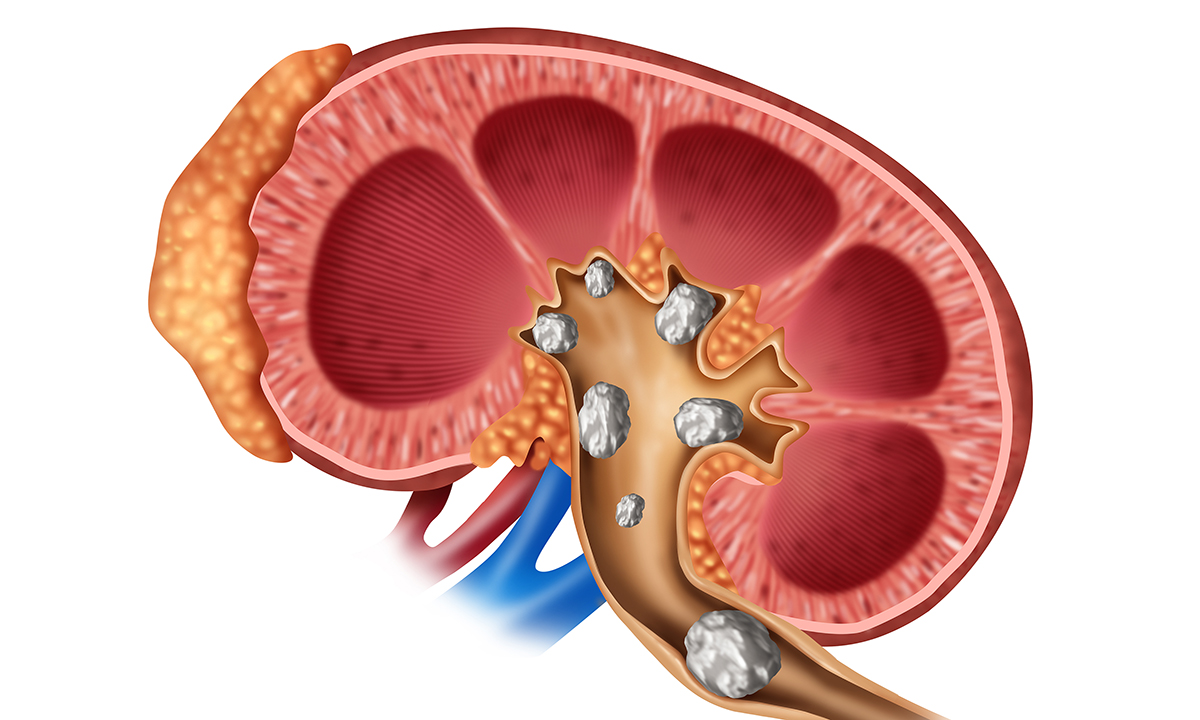

Introduzione sui calcoli renali

Sebbene i calcoli renali siano una delle patologie più frequenti dell’era moderna, la loro esistenza era conosciuta sin dall’antichità. I progressi tecnologici e l’avvento di procedure sempre meno invasive hanno sicuramente rivoluzionato i metodi di rimozione dei calcoli ai reni.

Tuttavia, le moderne tecniche endoscopiche non agiscono sulle cause della malattia ed hanno notevolmente aumentato i costi sanitari. Pertanto, oggigiorno, l’attenzione si è spostata sulla prevenzione della calcolosi renale che si basa essenzialmente su una corretta dieta.

Epidemiologia (torna su)

La prevalenza dei calcoli renali è compresa tra l’1% ed il 15% e può variare a seconda dell’età, del sesso, della razza e della distribuzione geografica. L’aumento di frequenza di questa patologia è un fenomeno globale. I dati epidemiologici europei, giapponesi ed americani dimostrano che sia l’incidenza che la prevalenza dei calcoli ai reni sono in aumento in tutto il mondo.

Tale aumento è in parte dovuto anche all’ implementazione ed alla crescente diffusione di procedure diagnostiche quali l’ecografia e la TAC. Gli uomini sono affetti dai calcoli renali con una prevalenza di 2-3 volte superiore alle donne. Tale differenza è dovuta ad un effetto protettivo esercitato dagli estrogeni sulla formazione dei calcoli.

Tuttavia, negli ultimi anni, la differenza dell’incidenza di questa patologia nei due sessi si sta assottigliando. Negli Stati Uniti la popolazione di razza caucasica è più frequentemente colpita dai calcoli ai reni rispetto agli altri ceppi etnici (asiatici, ispanici ed afroamericani). I calcoli ai reni sono rari negli individui di età inferiore ai 20 anni ed il picco di incidenza si registra nella fascia di età compresa tra i 30 ed i 60 anni.

La maggiore prevalenza al mondo si registra nel sud est asiatico. Per quanto attiene i fattori geografici e climatici, i calcoli ai reni sono più frequenti nei climi caldi, nelle aree desertiche e tropicali e durante la stagione estiva. Alla base di questa differenza vi è la fisiologica riduzione della diuresi che avviene con il caldo ed il conseguente aumento di rischio di formazione di calcoli.

Per lo stesso motivo, altro fattore di rischio è rappresentato dallo svolgere un lavoro che costringe ad essere a contatto con alte temperature (cuochi, lavoratori dell’industria siderurgica etc.). Il principale fattore di rischio per i calcoli renali è l’obesità: maggiore l’indice di massa corporea di un individuo maggiore il rischio di formazione di calcoli ai reni. Tipicamente i soggetti obesi presentano un’aumentata secrezione di ossalati, acido urico, sodio e fosforo.

Altri fattori di rischio sono il diabete, la sindrome metabolica e le patologie cardiovascolari. Gli studi epidemiologici suggeriscono che la dieta ed i fattori ambientali hanno un ruolo predominante sui fattori genetici nel determinismo dei calcoli ai reni. Bere abbondanti quantità di acqua è invece un riconosciuto fattore protettivo per i calcoli renali.

Calcoli renali cause (torna su)

Vi sono particolari tipi di individui che hanno una elevata predisposizione a formare calcoli renali. Questi individui vengono definiti con termine inglese “stone formers”, ossia individui formanti calcoli. I processi chimico-fisici che portano alla formazione dei calcoli renali comprendono una cascata di eventi che si verifica quando il filtrato glomerulare attraversa il nefrone.

Calcoli renali diagnosi (torna su)

La valutazione diagnostica di un paziente affetto da sospetta calcolosi urinaria si basa su:

- anamnesi

- esame del sangue

- esame delle urine

- esami radiologici

- analisi del calcolo

- valutazione metabolica

All’ anamnesi l’urologo ricercherà eventuali condizioni predisponenti quali:

- pregressi episodi di calcoli

- anamnesi familiare positiva per calcolosi

- malattie intestinali (in particolare diarrea cronica)

- fratture patologiche

- osteoporosi

- infezioni urinarie ricorrenti associate a calcolosi infettiva

- gotta

- Rene solitario

- Anomalie anatomiche

- Insufficienza renale

- Pregressa calcolosi di cistina, acido urico e/o struvite

- Dieta a base di alimenti potenzialmente causa di calcoli

- Assunzione di liquidi

- Farmaci

- Pregressi interventi per obesità (by pass gastrico)

Gli esami ematochimici permettono di rilevare la concentrazione nel sangue di:

- Calcio

- Ossalato

- Cloro

- Diossido di carbonio

- Fosforo

- Potassio

- Acido urico

- Azotemia

- Creatinina

- Paratormone (PTH)

La valutazione di questi parametri è di fondamentale importanza per comprendere le cause ed il tipo di calcoli.

All’ esame delle urine è possibile ricercare la presenza di cristalli nel sedimento urinario. Tramite il microscopio ottico l’analista valuta la forma dei cristalli, da cui si può risalire al tipo di calcoli di cui il paziente è affetto. Mediante l’urinocoltura si è in grado di ricercare la presenza di batteri produttori di ureasi potenziali causa di calcoli infettivi da struvite (Proteus, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Stafilococco).

Gli esami radiologici sono fondamentali per localizzare i calcoli renali e per avere informazioni sulla loro composizione. Solitamente vengono impiegati i seguenti esami:

- Radiografia diretta

- Ecografia apparato urinario

- Urografia

- TAC

I calcoli ai reni possono essere radio-opachi o radiotrasparenti.

I calcoli radiopachi sono quelli a base di:

- ossalato di calcio

- fosfato di calcio

- struvite

- cistina

I calcoli radiotrasparenti sono:

- acido urico

- xantina

- triamterene

Nel caso in cui si sospetti la presenza di un calcolo radiotrasparente sarà necessario eseguire una pieloureterografia oppure una TAC. Tramite l’imaging radiologico è inoltre possibile riconoscere eventuali anomalie anatomiche che predispongo alla calcolosi come una stenosi del giunto pieloureterale. In caso di episodio acuto (colica renale in atto) è preferibile non utilizzare esami che impiegano contrasti radiologici. In tali casi l’esame di scelta è l’ecografia, particolarmente utile per identificare uno stato di dilatazione degli ureteri e/o della pelvi renale (idronefrosi).

Laddove possibile, bisognerebbe sempre procedere con l’analisi microscopica del calcolo sia di tipo ottica che elettronica. Questo tipo di esame è in grado di stabilire con estrema precisione la composizione chimico-fisica dei calcoli espulsi spontaneamente o rimossi chirurgicamente.

Una valutazione metabolica estensiva si prefigge lo scopo di identificare l’alterazione e/o il processo patologico alla base della formazione di calcoli renali ed è fondamentale per impostare una corretta strategia di prevenzione nei confronti di potenziali futuri episodi di calcolosi.

La valutazione metabolica è indicata nei seguenti casi:

- individui che sono affetti cronicamente da calcolosi (cosiddetti “stone formers”)

- anamnesi familiare positiva per calcolosi

- patologie intestinali (in particolare diarrea cronica)

- fratture ossee patologiche

- osteoporosi

- infezioni urinarie ricorrenti associate a calcolosi

- gotta

- rene solitario

- anomalie anatomiche

- insufficienza renale

- calcolosi da cistina, acido urico e/o struvite

Una valutazione metabolica estensiva prevede l’esecuzione di tutti gli esami già descritti con l’aggiunta dell’ esame delle urine raccolte nelle 24 ore. Questo esame consiste nella valutazione delle urine raccolte durante un’intera giornata tramite appositi contenitori.

Tramite lo studio delle urine nelle 24 ore si possono acquisire dettagliate informazioni sulla quantità totale di urine prodotte giornalmente, sulla concentrazione giornaliera di singole sostanze come proteine, elettroliti e amminoacidi.

Calcoli renali sintomi (torna su)

La maggior parte dei calcoli renali è di piccole dimensioni, non provoca sintomi e vengono espulsi spontaneamente. Di contro, calcoli di grosse dimensioni, possono causare una ostruzione urinaria e generare dolore.

La colica renale viene tipicamente riferita dal paziente come un dolore acuto che insorge al fianco, alla schiena e/o dell’addome inferiore. Il dolore spesso inizia improvvisamente e poi si sposta diventando più intenso col tempo.

Terapia (torna su)

Terapia medica conservativa

Esistono alcune misure preventive e raccomandazioni generali che sono molto utili per la prevenzione di qualsiasi tipo di calcolosi a prescindere dal tipo specifico dei calcoli.

Acqua per calcoli renali (torna su)

Una delle principali misure preventive della calcolosi è bere molto. L’assunzione di liquidi dovrebbe essere tale da generare un volume urinario giornaliero di almeno 2 litri. Una abbondante diuresi previene la stagnazione delle urine ed aumenta la diluizione di sostanze che, precipitando, possono portare alla formazione di calcoli.

In particolare è utile bere un tipo di acqua con un basso contenuto di elettroliti. Anche i succhi di agrumi, come la limonata e l’aranciata, assunti quotidianamente insieme con un adeguato apporto idrico, aumento il volume urinario e la citraturia.

Calcoli renali dieta (torna su)

È di fondamentale importanza per la prevenzione e la terapia dei calcoli renali una appropriata alimentazione. Una corretta alimentazione e l’attività fisica possono ridurre l’incidenza della calcolosi. Questo paragrafo intende pertanto rispondere all’ annoso interrogativo: “calcoli renali: cosa mangiare?”.

Studi epidemiologici eseguiti in diverse aree geografiche hanno dimostrato che i calcoli renali hanno una maggiore incidenza nelle popolazioni che hanno un aumentato consumo di proteine animali.

Calcoli renali rimedi (torna su)

Una volta eseguito un corretto iter diagnostico e verificata l’alterazione metabolica alla base della formazione dei calcoli, è possibile instaurare una corretta terapia medica. Grazie alla comprensione del meccanismo patologico alla base della formazione di calcoli (descritto nel capitolo “calcoli renali cause”), è possibile prescrivere programmi terapeutici basati su terapie selettive.

Tuttavia, se queste terapie iniziali non funzionano, come eliminare i calcoli renali? Tramite la terapia chirurgica è possibile rimuovere la maggiore quantità possibile di calcoli in un unico intervento minimizzando le complicanze.

Colica renale (torna su)

La colica renale è la manifestazione clinica più dolorosa della calcolosi. La colica renale è determinata dal passaggio dei calcoli dal rene nell’ uretere attraverso il giunto pielo-ureterale. I calcoli ureterali possono causare una ostruzione parziale o totale al decorso dell’urina.

Questa ostruzione aumenta la pressione nei dotti collettori del rene determinando una distensione della pelvi, dei calici e della capsula renale.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

- Abdel-Halim, R.E., et al. A review of urinary stone analysis techniques. Saudi Med J, 2006. 27: 1462.

- Aboumarzouk, O.M., et al. Flexible ureteroscopy and laser lithotripsy for stones >2 cm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endourol, 2012. 26: 1257.

- Afshar, K., et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and non-opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015: CD006027.

- Akman, T., et al. Comparison of percutaneous nephrolithotomy and retrograde flexible nephrolithotripsy for the management of 2-4 cm stones: a matched-pair analysis. BJU Int, 2012. 109: 1384.

- Argyropoulos, A.N., et al. Evaluation of outcome following lithotripsy. Curr Opin Urol, 2010. 20: 154.

- Assimos, D.G., et al. The role of open stone surgery since extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. J Urol, 1989. 142: 263.

- Auer, B.L., et al. The effect of ascorbic acid ingestion on the biochemical and physicochemical risk factors associated with calcium oxalate kidney stone formation. Clin Chem Lab Med, 1998. 36: 143.

- Auge, B.K., et al. Ureteroscopic management of lower-pole renal calculi: technique of calculus displacement. J Endourol, 2001. 15: 835.

- Barcelo, P., et al. Randomized double-blind study of potassium citrate in idiopathic hypocitraturic calcium nephrolithiasis. J Urol, 1993. 150: 1761.

- Bas, O., et al. Management of calyceal diverticular calculi: a comparison of percutaneous nephrolithotomy and flexible ureterorenoscopy. Urolithiasis, 2015. 43: 155.

- Basiri, A., et al. Comparison of safety and efficacy of laparoscopic pyelolithotomy versus percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients with renal pelvic stones: a randomized clinical trial. Urol J, 2014. 11: 1932.

- Basiri, A., et al. Familial relations and recurrence pattern in nephrolithiasis: new words about old subjects. Urol J, 2010. 7: 81.

- Becker, G. Uric acid stones. Nephrology, 2007. 12: S21.

- Beltrami, P., et al. The endourological treatment of renal matrix stones. Urol Int, 2014. 93: 394.

- Bichler, K.H., et al. Indications for open stone removal of urinary calculi. Urol Int, 1997. 59: 102.

- Bichler, K.H., et al. Urinary infection stones. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2002. 19: 488.

- Binbay, M., et al. Evaluation of pneumatic versus holmium:YAG laser lithotripsy for impacted ureteral stones. Int Urol Nephrol, 2011. 43: 989.

- Biyani, C.S., et al. Cystinuria—diagnosis and management. EAU-EBU Update Series 2006. 4: 175.

- Bonkat, G., et al., EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections, in EAU Guidelines, Edn. published as the 32nd EAU Annual Meeting, London, E.A.o.U.G. Office, Editor. 2017, European Association of Urology Guidelines Office: Arnhem, The Netherlands.

- Borghi, L., et al. Comparison of two diets for the prevention of recurrent stones in idiopathic hypercalciuria. N Engl J Med, 2002. 346: 77.

- Borghi, L., et al. Nifedipine and methylprednisolone in facilitating ureteral stone passage: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Urol, 1994. 152: 1095.

- Borghi, L., et al. Randomized prospective study of a nonthiazide diuretic, indapamide, in preventing calcium stone recurrences. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol, 1993. 22 Suppl 6: S78.

- Borghi, L., et al. Urinary volume, water and recurrences in idiopathic calcium nephrolithiasis: a 5-year randomized prospective study. J Urol, 1996. 155: 839.

- Brandt, B., et al. Painful caliceal calculi. The treatment of small nonobstructing caliceal calculi in patients with symptoms. Scand J Urol Nephrol, 1993. 27: 75.

- Brocks, P., et al. Do thiazides prevent recurrent idiopathic renal calcium stones? Lancet, 1981. 2: 124.

- Burgher, A., et al. Progression of nephrolithiasis: long-term outcomes with observation of asymptomatic calculi. J Endourol, 2004. 18: 534.

- Cameron, M.A., et al. Uric acid nephrolithiasis. Urol Clin North Am, 2007. 34: 335.

- Campschroer, T., et al. Alpha-blockers as medical expulsive therapy for ureteral stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2014. 4: CD008509.

- Chan, L.H., et al. Primary SWL Is an Efficient and Cost-Effective Treatment for Lower Pole Renal Stones Between 10 and 20 mm in Size: A Large Single Center Study. J Endourol, 2017. 31: 510.

- Chen, K., et al. The Efficacy and Safety of Tamsulosin Combined with Extracorporeal Shockwave Lithotripsy for Urolithiasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Endourol, 2015. 29: 1166.

- Chew, B.H., et al. Natural History, Complications and Re-Intervention Rates of Asymptomatic Residual Stone Fragments after Ureteroscopy: a Report from the EDGE Research Consortium. J Urol, 2016. 195: 982.

- Chou, Y.H., et al. Clinical study of ammonium acid urate urolithiasis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci, 2012. 28: 259.

- Chow, G.K., et al. Medical treatment of cystinuria: results of contemporary clinical practice. J Urol, 1996. 156: 1576.

- Coe, F.L. Hyperuricosuric calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis. Adv Exp Med Biol, 1980. 128: 439.

- Coe, F.L., et al. Kidney stone disease. J Clin Invest, 2005. 115: 2598.

- Collins, J.W., et al. Is there a role for prophylactic shock wave lithotripsy for asymptomatic calyceal stones? Curr Opin Urol, 2002. 12: 281.

- Committee Opinion No. 723: Guidelines for Diagnostic Imaging During Pregnancy and Lactation. Obstet Gynecol, 2017. 130: e210.

- Cui, X., et al. Comparison between extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and ureteroscopic lithotripsy for treating large proximal ureteral stones: a meta-analysis. Urology, 2015. 85: 748.

- Curhan, G.C., et al. A prospective study of dietary calcium and other nutrients and the risk of symptomatic kidney stones. N Engl J Med, 1993. 328: 833.

- Curhan, G.C., et al. Comparison of dietary calcium with supplemental calcium and other nutrients as factors affecting the risk for kidney stones in women. Ann Intern Med, 1997. 126: 497.

- Danuser, H., et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy of lower calyx calculi: how much is treatment outcome influenced by the anatomy of the collecting system? Eur Urol, 2007. 52: 539.

- De, S., et al. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy versus retrograde intrarenal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 125.

- Dellabella, M., et al. Medical-expulsive therapy for distal ureterolithiasis: randomized prospective study on role of corticosteroids used in combination with tamsulosin-simplified treatment regimen and health-related quality of life. Urology, 2005. 66: 712.

- Dellabella, M., et al. Randomized trial of the efficacy of tamsulosin, nifedipine and phloroglucinol in medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral calculi. J Urol, 2005. 174: 167.

- Dello Strologo, L., et al. Comparison between SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 cystinuria patients and carriers: a need for a new classification. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2002. 13: 2547.

- Donaldson, J.F., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical effectiveness of shock wave lithotripsy, retrograde intrarenal surgery, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy for lower-pole renal stones. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 612.

- Drake, T., et al. What are the Benefits and Harms of Ureteroscopy Compared with Shock-wave Lithotripsy in the Treatment of Upper Ureteral Stones? A Systematic Review. Eur Urol, 2017. 72: 772.

- Dussol, B., et al. A randomized trial of low-animal-protein or high-fiber diets for secondary prevention of calcium nephrolithiasis. Nephron Clin Pract, 2008. 110: c185.

- Ebisuno, S., et al. Results of long-term rice bran treatment on stone recurrence in hypercalciuric patients. Br J Urol, 1991. 67: 237.

- El-Gamal, O., et al. Role of combined use of potassium citrate and tamsulosin in the management of uric acid distal ureteral calculi. Urol Res, 2012. 40: 219.

- El-Nahas, A.R., et al. A prospective multivariate analysis of factors predicting stone disintegration by extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: the value of high-resolution noncontrast computed tomography. Eur Urol, 2007. 51: 1688.

- Engeler, D.S., et al. The ideal analgesic treatment for acute renal colic–theory and practice. Scand J Urol Nephrol, 2008. 42: 137.

- Ettinger, B., et al. Chlorthalidone reduces calcium oxalate calculous recurrence but magnesium hydroxide does not. J Urol, 1988. 139: 679.

- Ettinger, B., et al. Potassium-magnesium citrate is an effective prophylaxis against recurrent calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis. J Urol, 1997. 158: 2069.

- Falahatkar, S., et al. Complete supine PCNL: ultrasound vs. fluoroscopic guided: a randomized clinical trial. Int Braz J Urol, 2016. 42: 710.

- Favus, M.J., et al. The effects of allopurinol treatment on stone formation on hyperuricosuric calcium oxalate stone-formers. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl, 1980. 53: 265.

- Fink, H.A., et al. Diet, fluid, or supplements for secondary prevention of nephrolithiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Urol, 2009. 56: 72.

- Fink, H.A., et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Guideline. Ann Intern Med, 2013. 158: 535.

- Garg, S., et al. Ureteroscopic laser lithotripsy versus ballistic lithotripsy for treatment of ureteric stones: a prospective comparative study. Urol Int, 2009. 82: 341.

- Geraghty, R., et al. Evidence for Ureterorenoscopy and Laser Fragmentation (URSL) for Large Renal Stones in the Modern Era. Curr Urol Rep, 2015. 16: 54.

- Gettman, M.T., et al. Effect of cranberry juice consumption on urinary stone risk factors. J Urol, 2005. 174: 590.

- Gettman, M.T., et al. Struvite stones: diagnosis and current treatment concepts. J Endourol, 1999. 13: 653.

- Ghoneim, I.A., et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy in impacted upper ureteral stones: a prospective randomized comparison between stented and non-stented techniques. Urology, 2010. 75: 45.

- Giedelman, C., et al. Laparoscopic anatrophic nephrolithotomy: developments of the technique in the era of minimally invasive surgery. J Endourol, 2012. 26: 444.

- Gilad, R., et al. Interpreting the results of chemical stone analysis in the era of modern stone analysis techniques. J Nephrol, 2017. 30: 135.

- Glowacki, L.S., et al. The natural history of asymptomatic urolithiasis. J Urol, 1992. 147: 319.

- Goldfarb, D.S., et al. Randomized controlled trial of febuxostat versus allopurinol or placebo in individuals with higher urinary uric acid excretion and calcium stones. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2013. 8: 1960.

- Gonzalez, R.D., et al. Kidney stone risk following modern bariatric surgery. Curr Urol Rep, 2014. 15: 401.

- Griffith, D.P., et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of Lithostat (acetohydroxamic acid) in the palliative treatment of infection-induced urinary calculi. Eur Urol, 1991. 20: 243.

- Guercio, S., et al. Randomized prospective trial comparing immediate versus delayed ureteroscopy for patients with ureteral calculi and normal renal function who present to the emergency department. J Endourol, 2011. 25: 1137.

- Gupta, M., et al. Treatment of stones associated with complex or anomalous renal anatomy. Urol Clin North Am, 2007. 34: 431.

- Gupta, N.P., et al. Infundibulopelvic anatomy and clearance of inferior caliceal calculi with shock wave lithotripsy. J Urol, 2000. 163: 24.

- Hara, A., et al. Incidence of nephrolithiasis in relation to environmental exposure to lead and cadmium in a population study. Environ Res, 2016. 145: 1.

- Heidenreich, A., et al. Modern approach of diagnosis and management of acute flank pain: review of all imaging modalities. Eur Urol, 2002. 41: 351.

- Hess, B., et al. Effects of a ‘common sense diet’ on urinary composition and supersaturation in patients with idiopathic calcium urolithiasis. Eur Urol, 1999. 36: 136.

- Hesse A, et al. Urinary Stones: Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention of Recurrence., In: Uric acid stones. 2002, S Karger AG,: Basel.

- Hesse, A., et al. Causes of phosphate stone formation and the importance of metaphylaxis by urinary acidification: a review. World J Urol, 1999. 17: 308.

- Hesse, A., et al. Quality control in urinary stone analysis: results of 44 ring trials (1980-2001). Clin Chem Lab Med, 2005. 43: 298.

- Hesse, A., et al. Study on the prevalence and incidence of urolithiasis in Germany comparing the years 1979 vs. 2000. Eur Urol, 2003. 44: 709.

- Hesse, A.T., et al. (Eds.), Urinary Stones, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention of Recurrence. 3rd edition. 2009, Basel.

- Hiatt, R.A., et al. Randomized controlled trial of a low animal protein, high fiber diet in the prevention of recurrent calcium oxalate kidney stones. Am J Epidemiol, 1996. 144: 25.

- Hofbauer, J., et al. Alkali citrate prophylaxis in idiopathic recurrent calcium oxalate urolithiasis–a prospective randomized study. Br J Urol, 1994. 73: 362.

- Holdgate, A., et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2005: CD004137.

- Holdgate, A., et al. Systematic review of the relative efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids in the treatment of acute renal colic. BMJ, 2004. 328: 1401.

- Hollingsworth, J.M., et al. Alpha blockers for treatment of ureteric stones: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 2016. 355: i6112.

- Honeck, P., et al. Does open stone surgery still play a role in the treatment of urolithiasis? Data of a primary urolithiasis center. J Endourol, 2009. 23: 1209.

- Hoppe, B., et al. The primary hyperoxalurias. Kidney Int, 2009. 75: 1264.

- Hubner, W., et al. Treatment of caliceal calculi. Br J Urol, 1990. 66: 9.

- Hyams, E.S., et al. Flexible ureterorenoscopy and holmium laser lithotripsy for the management of renal stone burdens that measure 2 to 3 cm: a multi-institutional experience. J Endourol, 2010. 24: 1583.

- Hyperuricosuric calcium stone disease, In: Kidney Stones: Medical and Surgical Management, Coe FL, Pak CYC, Parks JH, Preminger GM, Eds. 1996, Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia.

- Inci, K., et al. Prospective long-term followup of patients with asymptomatic lower pole caliceal stones. J Urol, 2007. 177: 2189.

- Isac, W., et al. Endoscopic-guided versus fluoroscopic-guided renal access for percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a comparative analysis. Urology, 2013. 81: 251.

- Ishii, H., et al. Outcomes of Systematic Review of Ureteroscopy for Stone Disease in the Obese and Morbidly Obese Population. J Endourol, 2016. 30: 135.

- Jarrar, K., et al. Struvite stones: long term follow up under metaphylaxis. Ann Urol (Paris), 1996. 30: 112.

- Jessen, J.P., et al. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy under combined sonographic/radiologic guided puncture: results of a learning curve using the modified Clavien grading system. World J Urol, 2013. 31: 1599.

- Johansson, G., et al. Effects of magnesium hydroxide in renal stone disease. J Am Coll Nutr, 1982. 1: 179.

- Kang, D.H., et al. Comparison of High, Intermediate, and Low Frequency Shock Wave Lithotripsy for Urinary Tract Stone Disease: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. PLoS One, 2016. 11: e0158661.

- Keeley, F.X., Jr., et al. Preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial of prophylactic shock wave lithotripsy for small asymptomatic renal calyceal stones. BJU Int, 2001. 87: 1.

- Kennish, S.J., et al. Is the KUB radiograph redundant for investigating acute ureteric colic in the non-contrast enhanced computed tomography era? Clin Radiol, 2008. 63: 1131.

- Keoghane, S., et al. The natural history of untreated renal tract calculi. BJU Int, 2010. 105: 1627.

- Khan, S.R., et al. Magnesium oxide administration and prevention of calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis. J Urol, 1993. 149: 412.

- Kim, S.C., et al. Cystine calculi: correlation of CT-visible structure, CT number, and stone morphology with fragmentation by shock wave lithotripsy. Urol Res, 2007. 35: 319.

- Kluner, C., et al. Does ultra-low-dose CT with a radiation dose equivalent to that of KUB suffice to detect renal and ureteral calculi? J Comput Assist Tomogr, 2006. 30: 44.

- Kocvara, R., et al. A prospective study of nonmedical prophylaxis after a first kidney stone. BJU Int, 1999. 84: 393.

- Kourambas, J., et al. Role of stone analysis in metabolic evaluation and medical treatment of nephrolithiasis. J Endourol, 2001. 15: 181.

- Kramer, G., et al. Role of bacteria in the development of kidney stones. Curr Opin Urol, 2000. 10: 35.

- Kumar, A., et al. A Prospective Randomized Comparison Between Laparoscopic Ureterolithotomy and Semirigid Ureteroscopy for Upper Ureteral Stones >2 cm: A Single-Center Experience. J Endourol, 2015. 29: 1248.

- Kumar, A., et al. A Prospective Randomized Comparison Between Shock Wave Lithotripsy and Flexible Ureterorenoscopy for Lower Caliceal Stones </=2 cm: A Single-Center Experience. J Endourol, 2015. 29: 575.

- Laerum, E., et al. Thiazide prophylaxis of urolithiasis. A double-blind study in general practice. Acta Med Scand, 1984. 215: 383.

- Lee, A., et al. Effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on postoperative renal function in adults with normal renal function. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2007: CD002765.

- Leijte, J.A., et al. Holmium laser lithotripsy for ureteral calculi: predictive factors for complications and success. J Endourol, 2008. 22: 257.

- Leusmann, D.B., et al. Results of 5,035 stone analyses: a contribution to epidemiology of urinary stone disease. Scand J Urol Nephrol, 1990. 24: 205.

- Locke, D.R., et al. Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy in horseshoe kidneys. Urology, 1990. 35: 407.

- Logarakis, N.F., et al. Variation in clinical outcome following shock wave lithotripsy. J Urol, 2000. 163: 721.

- Lojanapiwat, B., et al. Alkaline citrate reduces stone recurrence and regrowth after shockwave lithotripsy and percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Int Braz J Urol, 2011. 37: 611.

- Low, R.K., et al. Uric acid-related nephrolithiasis. Urol Clin North Am, 1997. 24: 135.

- Madbouly, K., et al. Impact of lower pole renal anatomy on stone clearance after shock wave lithotripsy: fact or fiction? J Urol, 2001. 165: 1415.

- Madore, F., et al. Nephrolithiasis and risk of hypertension. Am J Hypertens, 1998. 11: 46.

- Marchini, G.S., et al. Gout, stone composition and urinary stone risk: a matched case comparative study. J Urol, 2013. 189: 1334.

- Matlaga, B.R., et al. Drug-induced urinary calculi. Rev Urol, 2003. 5: 227.

- Mattle, D., et al. Preventive treatment of nephrolithiasis with alkali citrate–a critical review. Urol Res, 2005. 33: 73.

- Maxwell P.A. Genetic renal abnormalities. Medicine, 2007. 35: 386.

- McLean, R.J., et al. The ecology and pathogenicity of urease-producing bacteria in the urinary tract. Crit Rev Microbiol, 1988. 16: 37.

- Mi, Y., et al. Flexible ureterorenoscopy (F-URS) with holmium laser versus extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) for treatment of renal stone <2 cm: a meta-analysis. Urolithiasis, 2016. 44: 353.

- Miano, R., et al. Stones and urinary tract infections. Urol Int, 2007. 79 Suppl 1: 32.

- millman, S., et al. Pathogenesis and clinical course of mixed calcium oxalate and uric acid nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int, 1982. 22: 366.

- Mollerup, C.L., et al. Risk of renal stone events in primary hyperparathyroidism before and after parathyroid surgery: controlled retrospective follow up study. Bmj, 2002. 325: 807.

- Moon, K.B., et al. Optimal shock wave rate for shock wave lithotripsy in urolithiasis treatment: a prospective randomized study. Korean J Urol, 2012. 53: 790.

- Mortensen, J.T., et al. Thiazides in the prophylactic treatment of recurrent idiopathic kidney stones. Int Urol Nephrol, 1986. 18: 265.

- Moufid, K., et al. Large impacted upper ureteral calculi: A comparative study between retrograde ureterolithotripsy and percutaneous antegrade ureterolithotripsy in the modified lateral position. Urol Ann, 2013. 5: 140.

- Mufti, U.B., et al. Nephrolithiasis in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Endourol, 2010. 24: 1557.

- Nayan, M., et al. Variations between two 24-hour urine collections in patients presenting to a tertiary stone clinic. Can Urol Assoc J, 2012. 6: 30.

- Ng, C.S., et al. Contemporary management of cystinuria. J Endourol, 1999. 13: 647.

- Nicar, M.J., et al. Use of potassium citrate as potassium supplement during thiazide therapy of calcium nephrolithiasis. J Urol, 1984. 131: 430.

- Norman, R.W., et al. When should patients with symptomatic urinary stone disease be evaluated metabolically? J Urol, 1984. 132: 1137.

- Nouvenne, A., et al. New pharmacologic approach to patients with idiopathic calcium nephrolithiasis and high uricosuria: Febuxostat vs allopurinol. A pilot study. Eur J Int Med . 24: e64.

- Olvera-Posada, D., et al. Natural History of Residual Fragments After Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy: Evaluation of Factors Related to Clinical Events and Intervention. Urology, 2016. 97: 46.

- Osman, M., et al. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy with ultrasonography-guided renal access: experience from over 300 cases. BJU Int, 2005. 96: 875.

- Pak, C.Y., et al. Biochemical distinction between hyperuricosuric calcium urolithiasis and gouty diathesis. Urology, 2002. 60: 789.

- Pak, C.Y., et al. Management of cystine nephrolithiasis with alpha-mercaptopropionylglycine. J Urol, 1986. 136: 1003.

- Pak, C.Y., et al. Mechanism for calcium urolithiasis among patients with hyperuricosuria: supersaturation of urine with respect to monosodium urate. J Clin Invest, 1977. 59: 426.

- Parkhomenko, E., et al. Percutaneous Management of Stone Containing Calyceal Diverticula: Associated Factors and Outcomes. J Urol, 2017. 198: 864.

- Parks, J.H., et al. A single 24-hour urine collection is inadequate for the medical evaluation of nephrolithiasis. J Urol, 2002. 167: 1607.

- Passerotti, C., et al. Ultrasound versus computerized tomography for evaluating urolithiasis. J Urol, 2009. 182: 1829.

- Patel, T., et al. Skin to stone distance is an independent predictor of stone-free status following shockwave lithotripsy. J Endourol, 2009. 23: 1383.

- Pathan, S.A., et al. Delivering safe and effective analgesia for management of renal colic in the emergency department: a double-blind, multigroup, randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2016. 387: 1999.

- Pearle, M.S., et al. Meta-analysis of randomized trials for medical prevention of calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis. J Endourol, 1999. 13: 679.

- Pearle, M.S., et al. Prospective, randomized trial comparing shock wave lithotripsy and ureteroscopy for lower pole caliceal calculi 1 cm or less. J Urol, 2005. 173: 2005.

- Pearle, M.S., et al., Medical management of urolithiasis. 2nd International consultation on Stone Disease, ed. K.S. Denstedt J. 2008.

- Phillips, R., et al. Citrate salts for preventing and treating calcium containing kidney stones in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015: CD010057.

- Pickard, R., et al. Medical expulsive therapy in adults with ureteric colic: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 2015. 386: 341.

- Pierre, S., et al. Holmium laser for stone management. World J Urol, 2007. 25: 235.

- Pinheiro, V.B., et al. The effect of sodium bicarbonate upon urinary citrate excretion in calcium stone formers. Urology, 2013. 82: 33.

- Porpiglia, F., et al. Corticosteroids and tamsulosin in the medical expulsive therapy for symptomatic distal ureter stones: single drug or association? Eur Urol, 2006. 50: 339.

- Porpiglia, F., et al. Effectiveness of nifedipine and deflazacort in the management of distal ureter stones. Urology, 2000. 56: 579.

- Prakash, J., et al. Retroperitoneoscopic versus open mini-incision ureterolithotomy for upper- and mid-ureteric stones: a prospective randomized study. Urolithiasis, 2014. 42: 133.

- Premgamone, A., et al. A long-term study on the efficacy of a herbal plant, Orthosiphon grandiflorus, and sodium potassium citrate in renal calculi treatment. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health, 2001. 32: 654.

- Preminger, G.M. Management of lower pole renal calculi: shock wave lithotripsy versus percutaneous nephrolithotomy versus flexible ureteroscopy. Urol Res, 2006. 34: 108.

- Preminger, G.M., et al. 2007 Guideline for the management of ureteral calculi. Eur Urol, 2007. 52: 1610.

- Prien, E.L., Sr., et al. Magnesium oxide-pyridoxine therapy for recurrent calcium oxalate calculi. J Urol, 1974. 112: 509.

- Raboy, A., et al. Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy. Urology, 1992. 39: 223.

- Rassweiler, J.J., et al. Treatment of renal stones by extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy: an update. Eur Urol, 2001. 39: 187.

- Ray, A.A., et al. Limitations to ultrasound in the detection and measurement of urinary tract calculi. Urology, 2010. 76: 295.

- Rendina, D., et al. Metabolic syndrome and nephrolithiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the scientific evidence. J Nephrol, 2014. 27: 371.

- Riley, J.M., et al. Retrograde ureteroscopy for renal stones larger than 2.5 cm. J Endourol, 2009. 23: 1395.

- Rizzato, G., et al. Nephrolithiasis as a presenting feature of chronic sarcoidosis: a prospective study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis, 1996. 13: 167.

- Rodgers AL, et al. What can it teach us?, In: Proceedings of Renal Stone Disease 1st Annual International Urolithiasis Research Symposium, 2-3 November 2006., Evan A.P., Lingeman J.E. Eds. 2007, American Institute of Physics: Melville, New York

- Rodman JS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of uric acid calculi., In: Kidney Stones. Medical and Surgical Management, Coe FL, Pak CYC, Parks JH, Preminger GM., Eds. 1996, Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia.

- Rogers, A., et al. Management of cystinuria. Urol Clin North Am, 2007. 34: 347.

- Sahinkanat, T., et al. Evaluation of the effects of relationships between main spatial lower pole calyceal anatomic factors on the success of shock-wave lithotripsy in patients with lower pole kidney stones. Urology, 2008. 71: 801.

- Sanchez-Martin, F.M., et al. [Incidence and prevalence of published studies about urolithiasis in Spain. A review]. Actas Urol Esp, 2007. 31: 511.

- Santiago, J.E., et al. To Dust or Not To Dust: a Systematic Review of Ureteroscopic Laser Lithotripsy Techniques. Curr Urol Rep, 2017. 18: 32.

- Sarica, K., et al. The effect of calcium channel blockers on stone regrowth and recurrence after shock wave lithotripsy. Urol Res, 2006. 34: 184.

- Segura, J.W. Current surgical approaches to nephrolithiasis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am, 1990. 19: 919.

- Seitz, C., et al. Incidence, prevention, and management of complications following percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 146.

- Seitz, C., et al. Medical therapy to facilitate the passage of stones: what is the evidence? Eur Urol, 2009. 56: 455.

- Semins, M.J., et al. The effect of shock wave rate on the outcome of shock wave lithotripsy: a meta-analysis. J Urol, 2008. 179: 194.

- Sener, N.C., et al. Asymptomatic lower pole small renal stones: shock wave lithotripsy, flexible ureteroscopy, or observation? A prospective randomized trial. Urology, 2015. 85: 33.

- Sener, N.C., et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing shock wave lithotripsy and flexible ureterorenoscopy for lower pole stones smaller than 1 cm. Urolithiasis, 2014. 42: 127.

- Shekarriz, B., et al. Uric acid nephrolithiasis: current concepts and controversies. J Urol, 2002. 168: 1307.

- Shen, P., et al. Use of ureteral stent in extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for upper urinary calculi: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol, 2011. 186: 1328.

- Shokeir, A.A., et al. Resistive index in renal colic: the effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. BJU Int, 1999. 84: 249.

- Shuster, J., et al. Soft drink consumption and urinary stone recurrence: a randomized prevention trial. J Clin Epidemiol, 1992. 45: 911.

- Siener, R., et al. Dietary risk factors for hyperoxaluria in calcium oxalate stone formers. Kidney Int, 2003. 63: 1037.

- Siener, R., et al. The role of overweight and obesity in calcium oxalate stone formation. Obes Res, 2004. 12: 106.

- Silverberg, S.J., et al. A 10-year prospective study of primary hyperparathyroidism with or without parathyroid surgery. N Engl J Med, 1999. 341: 1249.

- Skolarikos, A., et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy 25 years later: complications and their

- Skolarikos, A., et al. Indications, prediction of success and methods to improve outcome of shock wave lithotripsy of renal and upper ureteral calculi. Arch Ital Urol Androl, 2010. 82: 56.

- Skolarikos, A., et al. Laparoscopic urinary stone surgery: an updated evidence-based review. Urol Res, 2010. 38: 337.

- Skolarikos, A., et al. Metabolic evaluation and recurrence prevention for urinary stone patients: EAU guidelines. Eur Urol, 2015. 67: 750.

- Skolarikos, A., et al. The Efficacy of Medical Expulsive Therapy (MET) in Improving Stone-free Rate and Stone Expulsion Time, After Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (SWL) for Upper Urinary Stones: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Urology, 2015. 86: 1057.

- Skolarikos, A., et al. Ureteropelvic obstruction and renal stones: etiology and treatment. Urolithiasis, 2015. 43: 5.

- Smith-Bindman, R., et al. Computed Tomography Radiation Dose in Patients With Suspected Urolithiasis. JAMA Intern Med, 2015. 175: 1413.

- Smith-Bindman, R., et al. Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med, 2014. 371: 1100.

- Soygur, T., et al. Effect of potassium citrate therapy on stone recurrence and residual fragments after shockwave lithotripsy in lower caliceal calcium oxalate urolithiasis: a randomized controlled trial. J Endourol, 2002. 16: 149.

- Srisubat, A., et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) versus percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) or retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) for kidney stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2014. 11: CD007044.

- Stamatelou, K.K., et al. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976-1994. Kidney Int, 2003. 63: 1817.

- Straub, M., et al. Diagnosis and metaphylaxis of stone disease. Consensus concept of the National Working Committee on Stone Disease for the upcoming German Urolithiasis Guideline. World J Urol, 2005. 23: 309.

- Strohmaier, W.L. Course of calcium stone disease without treatment. What can we expect? Eur Urol, 2000. 37: 339.

- Sun, X., et al. Treatment of large impacted proximal ureteral stones: randomized comparison of percutaneous antegrade ureterolithotripsy versus retrograde ureterolithotripsy. J Endourol, 2008. 22: 913.

- Sutor, D.J., et al. Identification standards for human urinary calculus components, using crystallographic methods. Br J Urol, 1968. 40: 22.

- Takei, K., et al. Oral calcium supplement decreases urinary oxalate excretion in patients with enteric hyperoxaluria. Urol Int, 1998. 61: 192.

- Tamm, E.P., et al. Evaluation of the patient with flank pain and possible ureteral calculus. Radiology, 2003. 228: 319.

- Tan, Y.M., et al. Clinical experience and results of ESWL treatment for 3,093 urinary calculi with the Storz Modulith SL 20 lithotripter at the Singapore general hospital. Scand J Urol Nephrol, 2002. 36: 363.

- Thompson, R.B., et al. Bacteriology of infected stones. Urology, 1973. 2: 627.

- Thomson, J.M., et al. Computed tomography versus intravenous urography in diagnosis of acute flank pain from urolithiasis: a randomized study comparing imaging costs and radiation dose. Australas Radiol, 2001. 45: 291.

- Tiselius, H.G. Standardized estimate of the ion activity product of calcium oxalate in urine from renal stone formers. Eur Urol, 1989. 16: 48.

- Tiselius, H.G., et al. Effects of citrate on the different phases of calcium oxalate crystallization. Scanning Microsc, 1993. 7: 381.

- Tokas, T., et al. Uncovering the real outcomes of active renal stone treatment by utilizing non-contrast computer tomography: a systematic review of the current literature. World J Urol, 2017. 35: 897.

- Topaloglu, H., et al. A comparison of antegrade percutaneous and laparoscopic approaches in the treatment of proximal ureteral stones. Biomed Res Int, 2014. 2014: 691946.

- Torricelli, F.C., et al. Impact of renal anatomy on shock wave lithotripsy outcomes for lower pole kidney stones: results of a prospective multifactorial analysis controlled by computerized tomography. J Urol, 2015. 193: 2002.

- Torricelli, F.C., et al. Semi-rigid ureteroscopic lithotripsy versus laparoscopic ureterolithotomy for large upper ureteral stones: a meta – analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int Braz J Urol, 2016. 42: 645.

- Trinchieri A CG, et al., Epidemiology, in Stone Disease, K.S. C.P. Segura JW, Pak CY, Preminger GM, Tolley D., Eds. 2003, Health Publications: Paris.

- Turk, C., et al. EAU Guidelines on Diagnosis and Conservative Management of Urolithiasis. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 468.

- Turk, C., et al. EAU Guidelines on Interventional Treatment for Urolithiasis. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 475.

- Turk, C., et al. Medical Expulsive Therapy for Ureterolithiasis: The EAU Recommendations in 2016. Eur Urol, 2016.

- Turney, B.W., et al. Diet and risk of kidney stones in the Oxford cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Eur J Epidemiol, 2014. 29: 363.

- Urine evaluation (in: Evaluation of the stone former), in 2ND International Consultation on Stone Disease, H.M. Assimos D. Chew B, Hautmann R, Holmes R, Williams J, Wolf JS, Editor. 2007, Health Publications.

- Van Der Molen, A.J., et al. CT urography: definition, indications and techniques. A guideline for clinical practice. Eur Radiol, 2008. 18: 4.

- von Unruh, G.E., et al. Dependence of oxalate absorption on the daily calcium intake. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2004. 15: 1567.

- Wabner, C.L., et al. Effect of orange juice consumption on urinary stone risk factors. J Urol, 1993. 149: 1405.

- Wagner, C.A., et al. Urinary pH and stone formation. J Nephrol, 2010. 23 Suppl 16: S165.

- Wall, I., et al. Long-term acidification of urine in patients treated for infected renal stones. Urol Int, 1990. 45: 336.

- Wang, H., et al. Comparative efficacy of tamsulosin versus nifedipine for distal ureteral calculi: a meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther, 2016. 10: 1257.

- Wang, H., et al. Meta-Analysis of Stenting versus Non-Stenting for the Treatment of Ureteral Stones. PLoS One, 2017. 12: e0167670.

- Wang, K., et al. Ultrasonographic versus Fluoroscopic Access for Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy: A Meta-Analysis. Urol Int, 2015. 95: 15.

- Wang, Q., et al. Rigid ureteroscopic lithotripsy versus percutaneous nephrolithotomy for large proximal ureteral stones: A meta-analysis. PLoS One, 2017. 12: e0171478.

- Wang, X., et al. Laparoscopic pyelolithotomy compared to percutaneous nephrolithotomy as surgical management for large renal pelvic calculi: a meta-analysis. J Urol, 2013. 190: 888.

- Wang, Y., et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of URSL, RPLU, and MPCNL for treatment of large upper impacted ureteral stones: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Urol, 2017. 17: 50.

- Wendt-Nordahl, G., et al. Do new generation flexible ureterorenoscopes offer a higher treatment success than their predecessors? Urol Res, 2011. 39: 185.

- White, W.M., et al. Predictive value of current imaging modalities for the detection of urolithiasis during pregnancy: a multicenter, longitudinal study. J Urol, 2013. 189: 931.

- Wimpissinger, F., et al. The silence of the stones: asymptomatic ureteral calculi. J Urol, 2007. 178: 1341.

- Wong HY, et al. Medical management and prevention of struvite stones, in Kidney Stones: Medical and Surgical Management, Coe & F.M. FL, Pak CYC, Parks JH, Preminger GM., Editors. 1996, Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia.

- Worcester, E.M., et al. New insights into the pathogenesis of idiopathic hypercalciuria. Semin Nephrol, 2008. 28: 120.

- Worster, A., et al. The accuracy of noncontrast helical computed tomography versus intravenous pyelography in the diagnosis of suspected acute urolithiasis: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med, 2002. 40: 280.

- Wu, D.S., et al. Indinavir urolithiasis. Curr Opin Urol, 2000. 10: 557.

- Wu, T., et al. Ureteroscopic Lithotripsy versus Laparoscopic Ureterolithotomy or Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy in the Management of Large Proximal Ureteral Stones: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Urol Int, 2017. 99: 308.

- Xiang, H., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of low-dose computed tomography of the kidneys, ureters and bladder for urolithiasis. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol, 2017. 61: 582.

- Yilmaz, E., et al. The comparison and efficacy of 3 different alpha1-adrenergic blockers for distal ureteral stones. J Urol, 2005. 173: 2010.

- Zarse, C.A., et al. CT visible internal stone structure, but not Hounsfield unit value, of calcium oxalate monohydrate (COM) calculi predicts lithotripsy fragility in vitro. Urol Res, 2007. 35: 201.

- Zhang, W., et al. Retrograde Intrarenal Surgery Versus Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy Versus Extracorporeal Shockwave Lithotripsy for Treatment of Lower Pole Renal Stones: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J Endourol, 2015. 29: 745.

- Zheng, C., et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus retrograde intrarenal surgery for treatment for renal stones 1-2 cm: a meta-analysis. Urolithiasis, 2015. 43: 549.

- Zheng, C., et al. Retrograde intrarenal surgery versus percutaneous nephrolithotomy for treatment of renal stones >2 cm: a meta-analysis. Urol Int, 2014. 93: 417.

- Zheng, S., et al. Tamsulosin as adjunctive treatment after shockwave lithotripsy in patients with upper urinary tract stones: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Urol Nephrol, 2010. 44: 425.

Specialista in Urologia ed Andrologia

Gallo Uro-Andrology Centre

Via Santa Lucia 97, 80132. Napoli

P.za del Corso 5, 84014, Nocera Inferiore (SA)

Mail: info@studiourologicogallo.it

Telefono: +390817649530 (fisso)

+393389838481 (mobile)

Sito Web: www.studiourologicogallo.it